Neuroarchitecture vs. Decoration: What’s the Difference?

Author: Dr. Natalia Botero

Picture this: A CEO buys a new apartment. The designer proposes an anthracite grey Minotti sofa, a Flos floor lamp, a black USM Haller shelving unit, a monstera plant in a Gandia Blasco planter. Impeccable. On trend. Approved.

Six months later, that same CEO is suffering from chronic insomnia. Struggling to concentrate in his home office. Feeling an irritability he can’t explain.

What went wrong?

It wasn’t the Minotti. It was ignoring his neurobiology.

Decoration dresses a space. Neuroarchitecture designs it so your brain can function.

They are two distinct disciplines. Both valuable. But confusing them comes at a cost that appears on no invoice: your rest, your mental clarity, your wellbeing.

In this article, you’ll discover why they are not the same — and when you need each one.

What is Decoration?

Decoration works with what you see. And it does it well.

Its territory is visual aesthetics: colours, furniture, textures, accessories, decorative lighting. Its goal is to create an attractive environment that reflects your personality and engages with current trends.

A good decorator is a valuable professional. They select coherent palettes, choose pieces that dialogue with the architecture, and create atmospheres that express who you are. That has merit.

The problem isn’t the decorator. The problem is assuming decoration solves everything.

When someone suffers from chronic insomnia, mental fatigue or unexplained irritability at home, they don’t need new cushions. They need to understand how that space is affecting their nervous system. And that falls outside the scope of decoration — not because the decorator is inadequate, but because it was never their territory.

It’s like asking a stylist to treat a medical condition. It isn’t their job.

Decoration dresses a space. Neuroarchitecture designs it so your biology can function.

Both are valuable. But confusing them carries an invisible cost.

What is Neuroarchitecture?

Neuroarchitecture works with what you cannot see. But what constantly affects you.

It is the discipline that studies how the built environment impacts your brain, nervous system and behaviour. It was formally established in 2003 with the creation of the Academy of Neuroscience for Architecture (ANFA), though its principles had been intuitively understood long before.

Its tools are not trend catalogues. They are fMRI, electroencephalograms, salivary cortisol measurement, galvanic skin response. Hard science applied to space.

Why does it matter?

Your brain processes 11 million bits per second of sensory information. Only 40 reach your consciousness. The remaining 99.9996% affects you without your noticing.

Light, geometry, materials, acoustics, orientation. These are all inputs your brain translates into chemistry: hormones, neurotransmitters, states of activation or relaxation.

Areas of impact:

- Nervous system: Activation (sympathetic) vs. Relaxation (parasympathetic)

- Circadian rhythms: Sleep-wake cycle, melatonin and cortisol production

- Cognitive processing: Attention, memory, decision-making, creativity

- Emotional regulation: Stress, wellbeing, motivation

An example:

A bedroom can look perfect. White linen sheets, a decorative plant, elegant indirect lighting. But if it has an east-facing window with direct morning light, LEDs at 6500K left on until 11pm, and the bed positioned in a cross draught between door and window, your brain is receiving contradictory signals: “activate” when it should be receiving “rest.”

Result: insomnia. Not from anxiety. From inadequate design.

Research confirms this: offices with dynamic circadian lighting show 18% higher cognitive performance (Mills et al., 2007). Hospital patients with a view of trees recover 8.5% faster (Ulrich, 1984).

Space is not neutral. It is programming you.

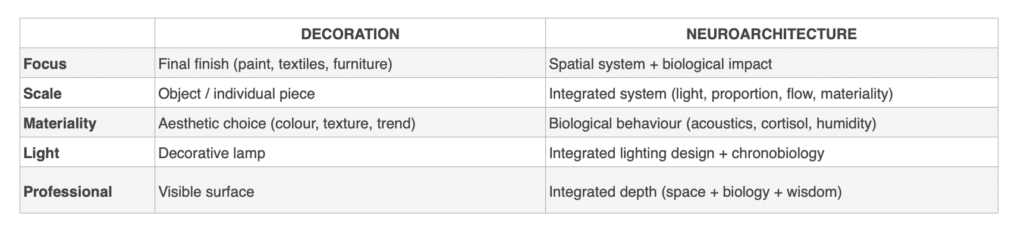

The 5 Key Differences

1. Focus: Finish vs. Spatial System

Decoration intervenes at the final layer: paint, textiles, furniture.

Neuroarchitecture operates from the structure of space: building orientation, volume proportion, spatial sequences, thresholds. And goes further: it understands how those architectural decisions affect the inhabitant’s nervous system.

The proportion of a room cannot be decorated. It is designed. And that proportion triggers neurological responses: high ceilings stimulate abstract thinking (Vartanian et al., 2013); curved spaces reduce amygdala activation — less alertness, more calm (Dazkir & Read, 2012).

Architecture + neuroscience. One without the other is incomplete.

2. Scale of Intervention: Object vs. Integrated System

The decorator selects pieces.

The architect designs systems: how light enters, how air circulates, how spaces relate to one another, what proportion void holds to solid.

The neuroarchitect adds a layer: measuring how that system affects those who inhabit it. Cortisol, melatonin, cognitive performance. Not intuition. Data. But without first mastering the spatial architecture, there is nothing to optimise.

3. Materiality: Texture vs. Biological Behaviour

Decoration chooses materials for aesthetics: colour, visual texture, trend.

Architecture chooses materials for behaviour: thermal mass, acoustic absorption, response to light, touch, ageing.

Neuroarchitecture adds: how the body responds. Wood is not simply “visually warm.” It has acoustic properties, regulates humidity, and reduces cortisol by 13% (Tsunetsugu et al., 2007). The architect already sensed that wood “feels right.” Now we know why.

4. Light: Lamp vs. Integrated Lighting Design

Decoration adds decorative lamps.

Architecture designs light: orientation of openings, window proportion, eave depth, surface reflection. Natural light is the architect’s most powerful material.

Neuroarchitecture specifies further: colour temperature according to time of day (6500K morning, 2700K evening), circadian transitions, elimination of blue light after 8pm. Because cool nocturnal light shifts your circadian rhythm by up to 3 hours (Gooley et al., 2011).

Without a good natural lighting design, artificial light cannot compensate. But without an understanding of chronobiology, even the finest lighting design remains incomplete.

5. The Professional: Surface vs. Integrated Depth

The decorator works at the visible layer. And does it well.

What distinguishes a professional in neuroarchitecture is not a title. It is depth of integration: understanding space as a system (light, proportion, flow, materiality), knowing how that system affects human biology, and — in the most complete cases — connecting with ancestral systems that have spent thousands of years observing the relationship between space and inhabitant.

That integration is not acquired on a course. It is built through years of study, practice and, above all, deep observation of how space affects people.

There are extraordinary decorators. There are architects who ignore human biology. The value lies in the combination of layers: spatial design + knowledge of the body + applied wisdom.

It is not who you are. It is what you know how to integrate.

Two Spaces, Two Approaches: Bedroom and Home Office

The theory is clear. Now let’s see how it translates into real decisions.

BEDROOM

Decoration approach:

Relaxing colour palette: pale blue, white, grey. Natural linen bedding (hygge trend). Minimalist bedside tables. Designer reading lamp. Sansevieria plant in the corner.

Result: Beautiful. Instagrammable. But do you actually rest?

Neuroarchitecture approach:

- Orientation: Bedroom ideally facing south-west. Less exposure to direct morning light = better nocturnal melatonin production.

Lighting design:

- Natural light: Blackout blind on east-facing window to prevent premature waking.

- Artificial light: Transition from 6500K (daytime) to 2700K (evening). Elimination of cool LEDs after 8pm.

Conscious materiality:

- Solid wood headboard (acoustic absorption + cortisol reduction).

- Natural textiles: cotton, linen. Polyester raises the nervous system’s frequency.

Spatial geometry:

- Bed away from cross draught between door and window (the reptilian brain remains on alert when positioned in a line of passage).

- No mirrors directly facing the bed (visual rebound prevents deep sleep).

Applied biophilia: Sansevieria — but not for aesthetics. It releases oxygen at night and purifies the air.

Measurable result: Reduced sleep latency, fewer nocturnal awakenings, higher proportion of REM sleep.

Science confirms: nocturnal blue light shifts the circadian rhythm by up to 3 hours (Gooley et al., 2011).

HOME OFFICE

Decoration approach:

Nordic-style desk. Ergonomic designer chair. Aesthetic organisation: pretty pen holders, a mood board. Decorative plant in the corner.

Result: Beautiful for photos. But productive?

Neuroarchitecture approach:

Strategic placement:

- Room with direct natural light. Ideally north-facing window = consistent light without glare.

- Avoid dark rooms: they produce daytime melatonin = drowsiness.

Lighting design:

- Morning natural light at 5000-6500K (activates cortisol = state of alertness).

- Minimum 500 lux at desk. Harvard studies: insufficient light = +40% cognitive errors.

Cognitive biophilia:

- Exterior view of nature (attentional restoration every 20 minutes — Kaplan’s Theory).

- 2-3 strategic plants: pothos, sansevieria. Air purification + reduction of mental fatigue.

Acoustics:

- Absorptive materials: linen curtains, jute rug = -15dB echo reduction.

- Keep ambient noise below 55dB. Above that threshold: -15% working memory.

Desk position:

- Facing a view (not a wall) = activation of the brain’s reward system.

- Mid-height ceiling supports concentration on specific tasks.

Measurable result: Sustained concentration for 3-4 hours (vs. typical 1-1.5h), reduction of headaches, +20-30% productivity.

Three minutes of nature viewing restores cognitive fatigue (Kaplan, 1995).

When Does Conscious Design Matter?

Always. But there are moments when its impact is critical.

When the space is no longer supporting you:

- Chronic insomnia or non-restorative sleep (you sleep 8 hours but wake up exhausted).

- Difficulty concentrating in your workspace.

- Recurring headaches with no clear medical cause.

- Anxiety or irritability that increases when you are at home.

- A feeling that your home drains you rather than recharges you.

When you have the opportunity to get it right from the start:

- Purchasing a new home.

- Full renovation.

- Seeking performance optimisation (CEOs, entrepreneurs, creatives).

Conscious Design: One Decision, Not Two Layers

There is a common misconception: the idea that architecture comes first (technical, invisible) and decoration comes after (aesthetic, visible). As though two separate professionals work in sequence.

That’s not how it works.

When solid oak is chosen over laminate, that is a biological decision — natural wood reduces cortisol by 13% (Tsunetsugu et al., 2007). And it is also an aesthetic decision: the warmth of the grain, the tactile texture, the honest ageing of the material.

They are the same act.

The orientation of the bed, the colour temperature of the light, the proportion of volumes — each of these decisions is simultaneously technical and aesthetic. There is no separate “functional” layer with a “decorative” one placed on top.

The beauty of the resulting space is not added at the end. It is the visible expression of biologically intelligent decisions.

A space designed through neuroarchitecture, biophilia and a deep understanding of how we inhabit is beautiful because it is right. Not the other way around.

Your Home as a Tool, Not Merely a Stage

For decades we designed homes as stages. Places where things happen. Beautiful backdrops for life.

But we overlooked something fundamental: space is not neutral. It is changing you constantly.

Every time you switch on cool light at 10pm, your brain suppresses melatonin. When you sleep in a cross draught, your nervous system stays on alert. When you work in a room without natural light, you produce daytime melatonin — and wonder why you feel so tired.

It is not your fault. No one taught you this.

But now you know.

Your home can be:

- A beautiful stage that ignores your biology.

- A tool that rests you, focuses you and recharges you — and that is also beautiful, because the care with which it was designed shows.

The difference is not aesthetic. It is the knowledge from which it is designed.

Final question:

How much is it costing you — in health, in performance, in wellbeing — to live in a space that was not designed for you?

Let’s talk about your space

If you feel your home isn’t supporting you as it should, perhaps it’s time to look at it through different eyes.

Dra. Natalia Botero

Architect specialising in Vastu Shastra, Neuroarchitecture, and Biophilic Design

www.espaciosparaser.com

Referencias científicas

1. Cajochen, C., et al. (2005). “High sensitivity of human melatonin, alertness, thermoregulation, and heart rate to short wavelength light.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

2. Gooley, J.J., et al. (2011). “Exposure to room light before bedtime suppresses melatonin onset and shortens melatonin duration in humans.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

3. Mills, P.R., et al. (2007). “The effect of high correlated colour temperature office lighting on employee wellbeing and work performance.” Journal of Circadian Rhythms.

4. Ulrich, R.S. (1984). “View through a window may influence recovery from surgery.” Science, 224 (4647), 420-421.

5. Nieuwenhuis, M., et al. (2014). “The relative benefits of green versus lean office space: Three field experiments.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied.

6. Kaplan, S. (1995). “The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework.” Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15 (3), 169-182.

7. Tsunetsugu, Y., et al. (2007). “Physiological effects of Shinrin-yoku (taking in the atmosphere of the forest).” Journal of Physiological Anthropology.

8. Vartanian, O., et al. (2013). “Impact of contour on aesthetic judgments and approach-avoidance decisions in architecture.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

9. Dazkir, S.S., & Read, M.A. (2012). “Furniture forms and their influence on our emotional responses toward interior environments.” Environment and Behavior.

10. Di Dio, C., et al. (2007). “The Golden Beauty: Brain response to classical and renaissance sculptures.” PLoS ONE.